12 minutes

N States

The Premise

We’ve come a long way since writing the first line of software. The premise of building software has always been simple: automate or solve a problem.

From creating straightforward inventory software that ran locally on machines to cloud infrastructure, one thing has always remained constant in software development.

States

A rudimentary definition of what a state is can be understood as the value of variables at any given point in time which is stored in the memory. This essentially means that the value of these variables represent the application’s state at the time of observation.

The concept of states laid the foundation of modern software development, and as time progressed, technologies came and went - the concept of states stayed with us, more or less the same.

Fast forward to today, we have state managers that help us persist and maintain our application’s state in a much more convenient and in an abstracted way.

The scope of this blog will involve Pinia.

Pinia is a state manager for NUXT, and it functions the same way as Redux. We create a global store which can be consumed by the components that need that data at any point of the application’s life cycle, and saves us from the prop-drilling hell.

But I recently came across a really interesting issue which I had to resolve and I realized that maintaining states with a store isn’t enough.

There needs to be a structure on how we handle these states, and this brought me to the following conclusion

‘There needs to be an internal state handler, which will handle the states declared in my store’

State Management

I love the concept of having a global store, which I can access from any where, and so far I haven’t really had any problems with this architecture until on Thursday, June 27th 2024.

The Problem

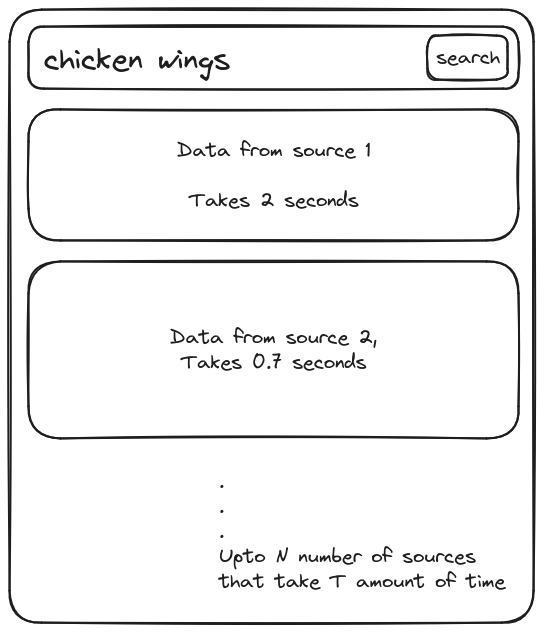

Consider the following component for an online food ordering website.

I search for ‘chicken wings’ in the search input and click search.

Now, I expect results for chicken wings, and for this example lets assume that the data will come from different sources, and each source will have a card for itself.

Here, we will make API calls to each source to request data for the search query when the user clicks the search button.

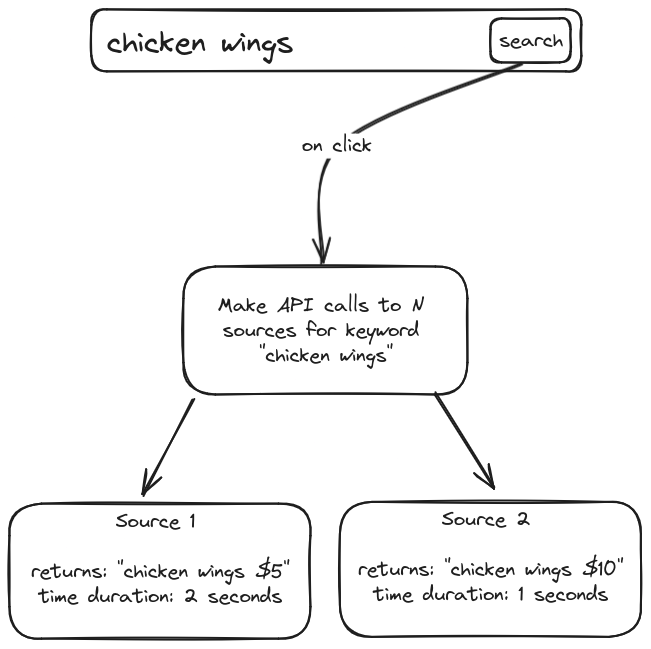

Lets understand the same with a diagram to register this visually as well.

This is where the problem begins to trickle down, but to understand the problem, let’s and handle the state for this component.

The Internal States

Let us understand the possible states we should/can handle to make the user experience better

Loading State

The first thing we’d like to implement is a loader i.e. whenever there is an API call, and new data is being fetched - we want the user to see a loader.

Success State

Once the data has been fetched, we’d like to show that to the user. For the sake of simplicity we will assume that that the reponse from the API is a JSON object that contains just two strings, which is the price of chicken wings from this particular source and a name.

{

name:'Chicken Wings',

price: '$5'

}

Failed State

Since we’re handling a success state, it is obvious that we need to handle a failed state as well.

We’re making a network request to an external source, and it is possible that the request might break in the future or not return anything at all.

So in a nutshell we have to maintain three states:

- Loading

- Success

- Failed

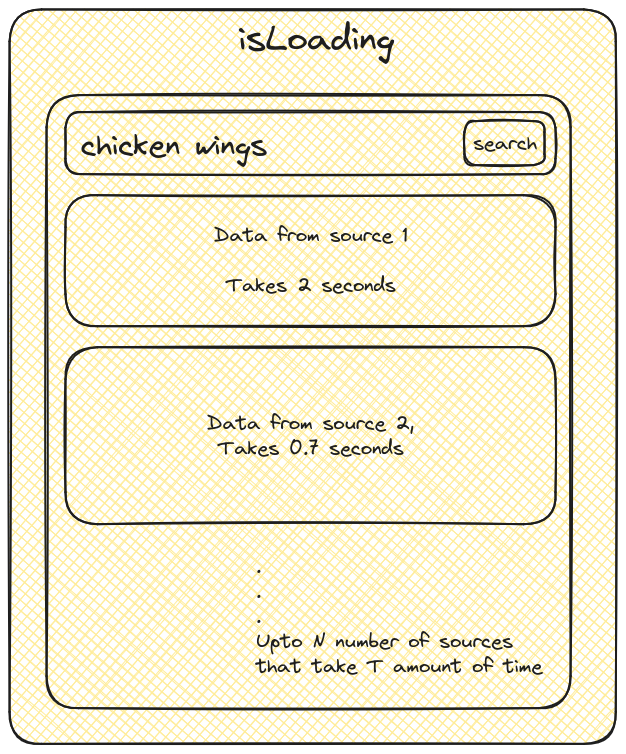

Pretty simple, so the general appraoch would be to create a boolean value called:

isLoading

Now understand that this boolean value defines the state of the entire component.

The general approach here would be to set isLoading to true whenever we request data from an API and once the fetching of data is complete, we set isLoading to false.

If we have the data, we render it to the UI - this is our success state otherwise we show an error or don’t show the card in our UI at all - this is our failed state.

Fundamentally this will work, but the caveat here is that it will work as long as there in one source of data.

This is our problem

Let’s dive a little deeper to understand why this is a problem.

The UI

On the frontend we recieve an array of data which we parse into our component as props.

Here’s what the data that we are passing to our component looks like:

response: [

{

name:'Chicken Wings',

price: '$5'

},

{

name:'Chicken Wings Spicy',

price: '$10'

}

]

On the UI front, we will render the cards inside a for loop which runs for the length of the response of the array.

Now look at the diagram below.

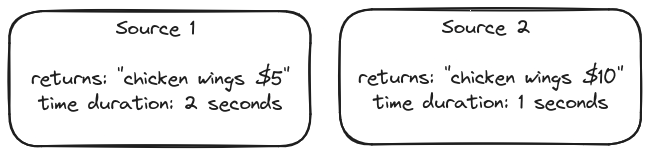

We will be making separate API calls to get data the from these two sources, and each of these API calls will take their own time and return their own data.

There is a possibility that source-1 might return some data in 2 seconds while source-2 might not return data at all even after 10+ seconds.

But from our current appraoch, isLoading state governs the entirety of the component.

Each API call we make will update the same isLoading variable and if any of the APIs take, let’s say, a maximum of T amount of time, our component will be visible to us after that time even though we had data which we could show to the user from other sources.

This leads to bad user experience.

One might argue that we can simply make two different isLoading variables for each of the sources we are making a call to.

But if have

nnumber of sources will we makennumber ofisLoadingvariables in our store to govern our differnent API calls?

Is this really maintainable in a production codebase where we might have 100+ different API endpoints, each requiring their own maintainable state?

And countless more such question will pop up when you attempt to scale it further. Take an ecommerce website for example. There are so many components that are decoupled and function independently, decoupled from other components and serving their own specific use case.

From the search bar to search the products to an individual filters on the result page, each one of them will maintain their own state(s). For example, if a page has 10 different components and one of them is loading while the rest aren’t; it’s obvious that we will maintain the state of that component within that component itself but again, since different developers have different approaches - each component’s state will be handled differently.

It is also not necessary that each component will require a store of its own but might have to handle a success/failed or a loading condition.

This brings us to the final revelation before we start implementation of a simple yet powerful architecture that all the developers can follow through.

In our current scenario, we are working with Pinia, which is similar to Redux. The keyword that is used to describe these libraries is that they are 'State Management' libraries.

So what is the big revelation?

State Management != State Handling

The state management library we are using, be it Redux or Pinia, they provide us with a centralized method to deal with the local variables that compose the state of that particular component, service or process in general.

We are building an architecture to “handle” our states, not “manage” them.

The Solution

To implement the solution, I will use TypeScript, since we’re using a framework that uses JS/TS; but the theory of this approach can be applied to any technical stack or language.

This is not a tutorial around JavaScript, NUXT or Pinia, so I will not attach screenshots or a step by step guide as to how to setup a store, and create variables and create a new project.

We will start by creating a new a TypeScript file that will define the state of our processes like so:

export type State = 'success' | 'failed' | 'loading' | 'idle'

export interface APIState {

status: State,

message?: String,

data?: Object

}

Now that we have defined our interface and a type that our state will adhere to, let us quickly understand it.

If you have worked with TypeScript before, this would have made sense to you already and how you might use it but do read it ahead. hehe.

Here, we have defined a type called State;

export type State = 'success' | 'failed' | 'loading' | 'idle'

Any variable that you create of type State, will only have either of the specified four values. i.e.

'success' | 'failed' | 'loading' | 'idle'

Making use of this type, we have created an interface called APIState.

We will understand this interface in depth as we move further with the implementation of our state handler.

export interface APIState {

status: State, // <---

message?: string,

data?: object

}

Now, let’s go back to our problem statement that arose because of different sources of chicken wings.

In our Pinia Store, or if you have a different stack you can create this state where ever you would manage the isLoading state. We will create a new variable that will handle the state of a singular chicken wing source like so:

let chickenWingSource1 = <APIState> {

//

}

In the above example we have a schema available for this object that is imposed by the type APIState. The variable that we have just created chickenWingSource1 can have the values defined by our interface with type safety.

This ensures that every developer in the team or if you’re an individual even, everyone always follows the same structure to maintain the state.

To make more sense to what we’ve done so far, let’s complete the definition of this state and define a state for our other chicken wing source as well.

let chickenWingSource1 : APIState = {

/**

* Type safe, using idle as an initial state when we have no

* data nor are we making any request

*/

status: 'idle',

/**

* Optional.

* message can be used to pass/store any relevant information

* to the the UI or any other part of your app that will

* consume this state.

*

* Setting it as an empty string initally.

*/

message: '',

/**

* Optional.

* data can be used to pass the entire response of data of

* state. You can extend the data and make it type safe

* by defining your response schema.

*/

data: {}

}

Once we define both of our states, the result may look something like this:

let chickenWingSource1: APIState = {

status: 'idle',

message: 'Source 1 - Idle',

data: {}

};

let chickenWingSource2: APIState = {

status: 'idle',

message: 'Source 2 - Idle',

data: {}

};

Now, we know that these states will change according to the API response, so we will have to update the states accordingly.

For this, we can create a composable or a utility method that is available globally in our code base and it will look something like this:

export const useStateModifier = (

stateName: APIState,

newState: State,

newMessage?: string,

newData?: object,

) => {

stateName.status = newState;

if(newMessage) {

stateName.message = newMessage;

}

if(newData){

stateName.data = newData;

}

}

The utility method that we have defined above takes the following arguments that are essentially the keys that we defined in our APIState interface, to ensure type safety and auto-complete.

stateName: APIState-> Pass the state object of typeAPIStatewhich you want to update.newState: State-> Pass the new state of typeStateto which you want to update your current state to.message: string-> Optionally pass a message of typestringfor the state update.data: object-> Optionally pass some data of typeobjectto into your state.

This method takes the state object which you are using to handle the API/process and also takes the new state to which you want to update it to, as required functional arguments. The other two arguments are optional.

The method first updates the state to the value that you have passed, and after that the method checks if it has received any value for the parameter message and data and updates them accordingly.

Now let’s make use of this utility method to conveniently update the state of our API calls to individually show the status of each chicken wings source.

For this, I will write a dummy function that will make API call(s) to all the sources(endpoints) of chicken wings.

For the sake of simplicity, the function will make only one call at a time and we can wrap the function in a loop to make successsive API calls.

Here’s what the dummy function looks like:

const getFoodDetailsFromDifferentSources = async (

stateName: APIState,

endpoint: string

) => {

try {

useStateModifier(stateName, 'loading', 'Loading...');

stateName.data = await fetch('api.source1.com/wings');

// A very crude and rudimentary check on data.

// Don't hate me for this.

if (stateName.data) {

useStateModifier(

stateName,

'success',

'Fetched chichen wing data from source'

);

} else {

throw Error('Failed to fetch chicken wing data from source')

}

}

catch (e: any) {

useStateModifier(stateName, 'failed', e);

}

}

As you can notice that we are updating the state using the useStateModifier method to update the state of our process according to the data that we get and whether we are still fetching the data or not.

To make things even more convenient, I am storing the API response in the state variable itself in the data field. You can handle the response differently, that is completely up to you and the tech stack that you are using.

Let’s go back to the UI and see how we can elevate this architecture to show the correct UI to our user based on the state.

The UI - Again

Since this entire blog has been centered around NUXT and Pinia, I will write my component in NUXT 3 only. Though there is nothing strict about the UI, you can recreate it in any framework or stack, as long as you’ve understood the concept theoretically.

<template>

<div>

<div v-if="chickenWingsStore.chickenWingsSource1.status === 'loading'">

<p>Loading...</p>

</div>

<div v-else-if="chickenWingsStore.chickenWingsSource1.status === 'success'">

<p>Success! chicken wings loaded.</p>

</div>

<div v-else-if="chickenWingsStore.chickenWingsSource1.status === 'failed'">

<p>Error: {{ apiState.message }}</p>

</div>

<div v-else-if="chickenWingsStore.chickenWingsSource1.status === 'idle'">

<p>Idle. Waiting for chicken wings.</p>

</div>

</div>

</template>

<script setup lang="ts">

const chickenWingsStore = useChickenWingsStore();

</script>

Here in, I have created a component in NUXT 3, where I am using the Pinia store that we created to manage our API state which is now being handled by the state handling architecture that we have built.

Based on how and when we update the states according to our business logic - the UI will update on it’s own because at any given moment it can only be in success, failed, loading or idle state.

That wraps up this post. I hope you enjoyed this little read. Please feel free to drop your suggestions, critiques and talk about it in general.

You can always reach out to me on Discord @dh00mk3tu

Cheers to good engineering!